Design Like a Developer: How to Build Garments That Scale from Sketch to Shelf

Scaling smart: designing products that evolve, repeat, and deliver at volume

Good morning everyone.

This week I am diving into the world of product design and development, more specifically, building garments that can scale.

In my last Friday Thread instalment, I discussed the inners workings of developing a well balanced range, discussing the key balance between margin drivers and hero products which you can read below;

This week, I will explore the steps and processes to take in order to build a rock solid foundation when it comes to product to give you the best chance of both short term and long term success.

The Science of Fit

The greatest source of product returns is unsurprisingly fit. Getting the fit of your garments correct from the outset is one of the most important elements to scaling your products.

A very common mistake would be launching your products without serious consideration to how the product fits, leading to a high return rate and distrust from the customer.

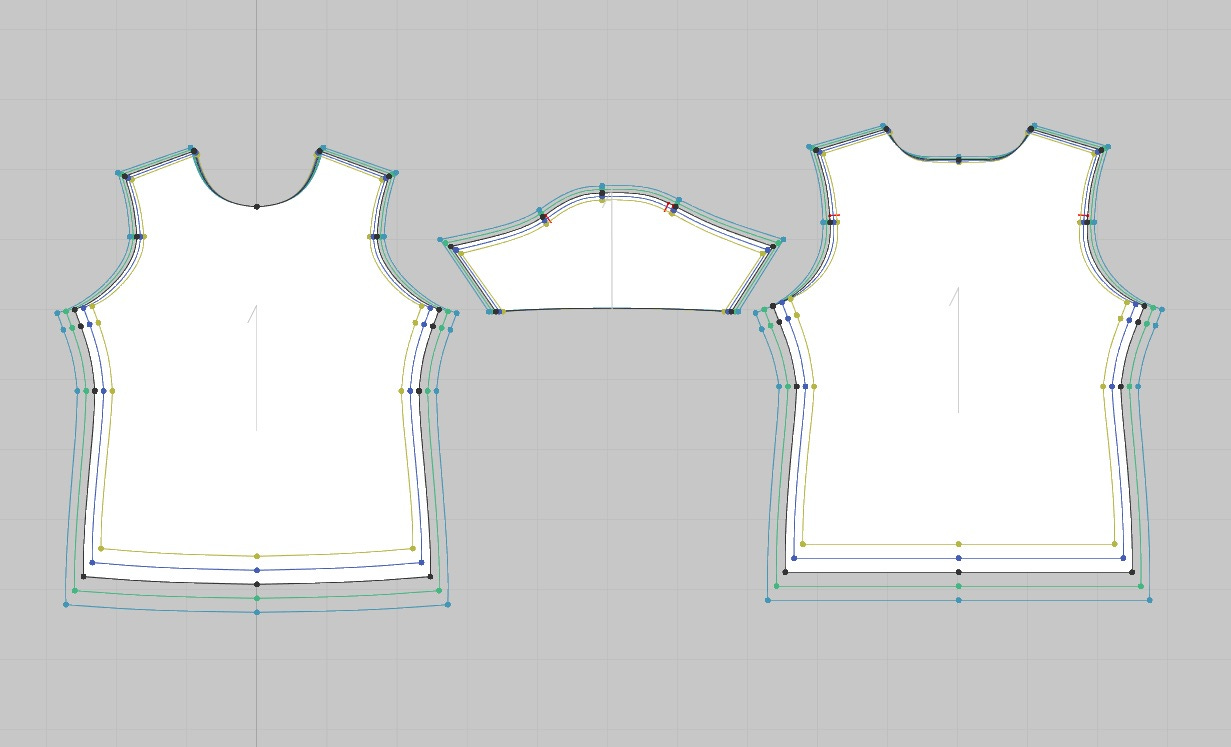

Getting your base blocks created is one of the most fundamental things about nailing fit. I’ll be honest, when it comes to fit, I am no expert in the process, so I reached out to Philippa Cooper (who is), and has decades of experience in product development and pattern design to run us through the fundamentals of fit. If you want to understand all things related to technical product development and sizing, I highly suggest you follow her on LinkedIn, which you can do so here.

What is a Base Block?

A base pattern block is a simple foundational pattern that is based on your customer profile and ideal customer body measurements that can be used as a starting point for developing new products to ensure consistent fit within your brand, help communicate fit information more clearly internally and externally and reduce garment returns. It can also help speed up the sampling process.

Garment blocks can help ensure your garment fit is consistent within your range. Key measurements like your sleeve lengths, leg lengths, centre front/ centre back garment lengths all stay consistent within your range, and the garment ease can be adjusted as you go to suit the assigned fabric. Brands that use a few signature fabrics benefit the most with garment blocks because they have consistent fabric properties.

Ideally you want a block for stretch fabrics and non-stretch fabrics as the garment ease will be quite different.

You may also want a block for the desired fit you are designing for, such as a relaxed fit vs an athletic fit, because the amount of garment ease can vary a lot even within base layers.

For example, an athletic fit t-shirt might have -1 inch ease on the chest, whereas a loose fit t-shirt might have +2 inch ease on the chest.

In outerwear this can vary even more, some fitted jackets might have a garment ease of 12cm, whereas some loose jackets might have a garment ease of up to 30cm.

Blocks can be drafted in 2D or 3D on software such as Gerber and Clo3D, either from scratch or reverse engineer a best seller. I have reviewed the fit of a whole range before and compared the customer feedback and sales data to create a block library for them to provide more clarity and consistency in their sizing.

If you have graded, modular blocks that is set up in your 2D and 3D pattern libraries then your workflow will be quicker and simpler, and sampling should be faster. Fabric properties are also key as they impact the fit of a garment so much.

Modular blocks could be different sleeve types or fitted waist, vs elasticated waist, full zip, vs quarter zip etc.

These blocks can then also be sent to your manufacturer so if you are manufacturing in different countries, the fit should still be consistent.

Modular Design Thinking

Modularity is probably not the first thing you think of when designing sportswear garments, but in order to scale, it can help form a crucial foundation. What is modularity though?

In the context of sportswear, a modular component is a design element that can be reused or adapted across multiple styles, fits, or product categories. A few examples below;

Signature pocket system that works across jackets and shorts

A panelling technique that can be scaled across different body types and sizes

A collar construction that is adapted across different tops

An real-world example where modularity has been used is the upcoming launch of Goldwin 0’s performance product.

There is an argument in this case that the concept is over used, but when integrated thoughtfully, it can be a powerful tool to work with, and here’s why.

Function-Led Design Language

I’ve spoken previously about the importance of design language when building a memorable brand. Modular elements can provide this by offering unique identifiers which are both functional, yet identifiable to the brand.

Whilst the Goldwin 0 example is very obvious, there are other brands that showcase this in more subtle ways. Arc’teryx is one brand that immediately comes to mind, utilising bonded pocketing within their modular design language.

Utilised across multiple styles and categories, the branded bonded pocket has become synonymous with the Arc’teryx design DNA. This modular design component doesn’t simply provide a functional element to their garments, but instead, an identifiable element which others can immediately recognise.

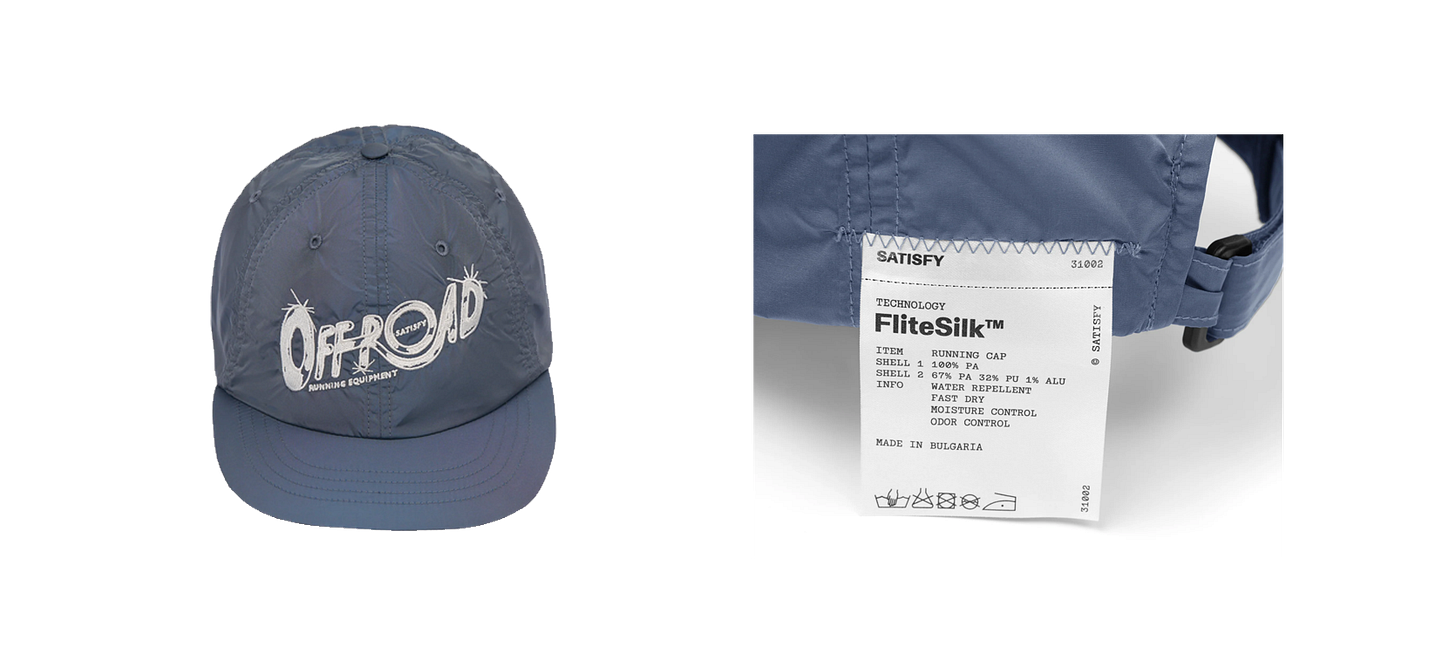

Another example of this is Satisfy’s tearaway label. Although some may argue it’s not a design element, a textile label stating composition is mandatory in EU regulations, and often gets attached to the inside of the garment, out the way of any design thinking.

Satisfy, however, flipped the script - making what is seen as a very un-aesthetic element, and positioning it in a way that reflects their design DNA.

It’s of course, also modular, easily adapted across a number of styles and categories, even in some of their accessories such as caps.

Component Libraries: Building Blocks of Style

One of the foundations of modular design thinking is the ability to build blocks of components that we can pick from to use across our garments. Component libraries are a specific set of garment elements that can be reused, combined or iterated across different designs.

In the case of sportswear, this could be as simple as specific branded zipper that is used for shorts, jackets and trousers. Or, in the example of lifestyle brand Aries, they use a specific drawcord across multiple styles;

To implement this, create a digital asset library using software like CLO3D or Illustrator, with annotations and sizing rules. For example, the drawcord length Aries uses for their hoodies is significantly longer to those used in the sweatpants, and this is why sizing rules within the asset library is important.

One crucial element to creating a component library is that it helps speed up design and development times. Consider how long it would take if Arc’teryx had 10 different pocket designs across categories - they would have to design them, develop them and test them. By having the consistent bonded pocket design, they have only had to design that one pocket, get it tested, and then adapt it across different products. Of course, there will have to be testing across the different fabrics and applications, but once that bonded pocket is tested, it can stay in the component library season after season.

Material Zoning

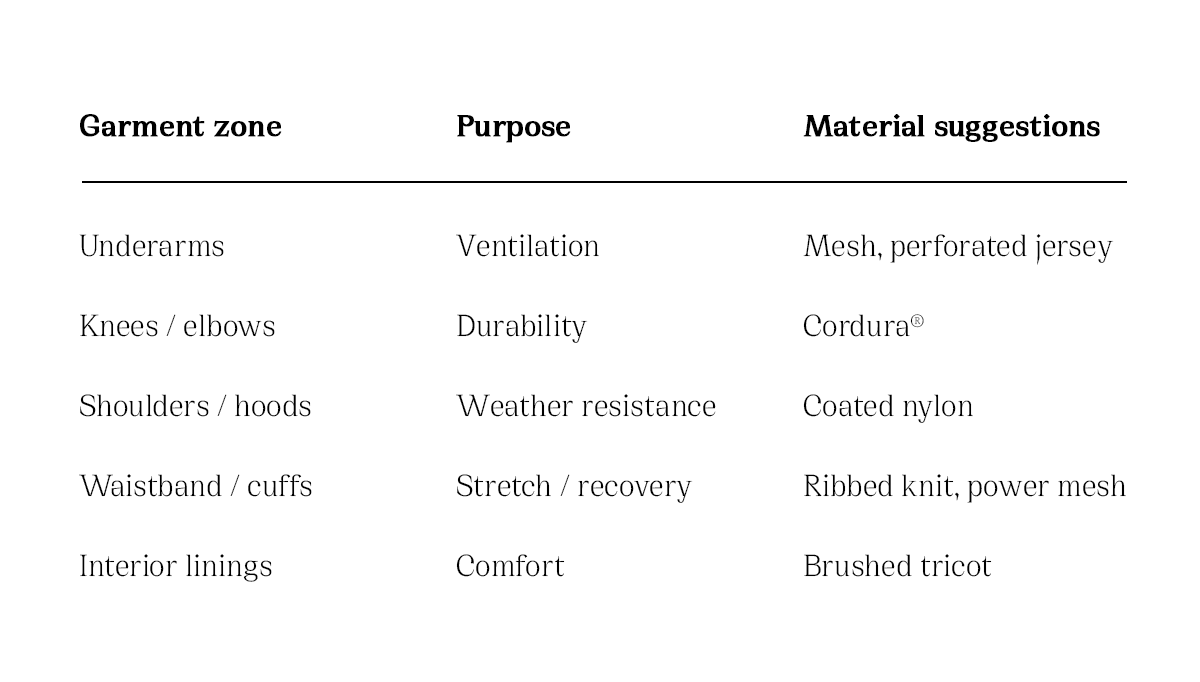

Material zoning is the practice of integrating different fabrics and finishes to specific zones of garments based on how that area should perform.

Sportswear is performance product, and we want to optimise the garment for function as best we can. Material zoning is a great way to improve the technical performance of a garment, whilst adding and contributing to the design DNA of a brand.

Below is a table showing some of the common material zones, the purpose of them, and what fabric I would suggest;

There are plenty of examples in sportswear that utilise the power of material zoning. It’s probably more common to see in premium and higher end brands because it involves more cut and sew, additional fabric and further testing.

Material zoning not only provides a functional element, it can - as seen in the Satisfy and District Vision example above - provide a visual aesthetic. When you’re designing a garment, the zones should be thought out at the sketch stage, not just at tech pack stage. You can use colour blocking to highlight certain areas, or use subtle hidden transitions for a less obvious aesthetic.

Versioning and Iteration

When you’re building a product, especially one which you’re building to scale, don’t treat it as a final product. As brands, we’re often stuck in this constant battle between newness and ensuring quality. From my experience, it’s incredibly difficult to get new products to market that are of high-quality and gone through rigorous testing.

As a new brand, there is definitely the internal pressure to ensure that the product your bringing to the market is perfect. However, I’d argue that perfection isn’t achieved through internal design and development. Products should evolve through prototyping, user feedback and successive versioning.

When I started Torsa, I remember spending years trying to make the product perfect. I remember every prototype that came in, I’d want to add something else, or refine the smallest of details. Whilst this may be seen as a good thing, what it ended up doing was just significantly reducing our speed to market. The product, although important, is just one element among many that will persuade customers to buy from your brand. You’re better getting a product to market faster, getting real life feedback, and refining and bettering the latter versions. R.A.D, the popular cross-training show from the UK followed this exact method. They launched a Version 1, learned, gathered feedback, and went on to iterate to achieve something better, recently launching their Version 2.

Prototype Like Your Debugging

It’s first important to note, the depth in which you go with each individual product is determined by your business as a whole. What I mean by this is that I wouldn’t expect you to go through the process of versioning and iteration on every single product you luanch. However, if you’re launching with a single product which is led by true innovation, then this technique is valid.

Footwear is a perfect example to use this method, but in apparel, there may be a certain garment that you’re throwing loads of resources in, looking to position it as a hero product for years to come. This is another example where versioning might make sense.

Treat each prototype as a test case. For example, if you’re creating a running short designed for Marathon length running, look to identify any issues that could arise. This could be something like reviewing whether the bonded seam starts chafing at a certain distance, or whether the weight of the short increases drastically when exposed to sweat.

Log the issues and assign fixes for the next prototype (eg. reposition bonded seam, or swap out shell fabric for something lighter). These logs become internal change logs - helping the design team track garment evolution season after season.

Material Consistency: Think Supply Chain Early

Material consistency is the linchpin between your design concept and real-world scalability. Whether you’re making 50 pieces or 5,000 pieces, consistency ensures your garment performs, feels and looks the same from sample room to store shelf.

Why it matters in sportswear?

In performance apparel, small inconsistencies can lead to big consequences. Whilst in lifestyle apparel, a slight difference in stretch recovery of a jersey fabric won’t result in any serious issues, if the same happens to a pair of stretch jersey compression leggings, you’re going to run into some serious problems.

In the same way, if your products colour shift or pill after they have launched, it’s going to erode trust with your customer. When I worked at lululemon, pilling of their signature Align legging was the number one reason for damaged returns. In defence to lululemon, the pilling was a result of constant friction, usually coming as a result of weight training. However, the Align legging was designed for low impact, low friction training such as yoga.

However, this just goes to show the intricacies of product. Whilst the Align was designed and developed for yoga, many customers adapted it for the gym instead. This adaptation shed light on the issue of pilling. Now, I am not saying that each garment can cover every base, but it just goes to show the importance of product testing. So, how can we ensure we’re choosing the right materials for our products.

Choose Repeatable, Scalable Fabrics

You want to ensure your products have the capacity to scale. One key element of this is making sure that the fabric you choose has guaranteed volume and consistent specs.

The last thing you want to do is put in the time and resources into sourcing, designing, developing and testing a fabric only for the fabric mill to say at the last minute it’s been discontinued.

A good checklist to follow when you’re working with fabric mills may look something like this;

Can run large volumes of fabrics with low variance

Have documented QC processes and certifications (e.g. ISO, Bluesign)

Provide swatch libraries with verified shrinkage, stretch, and colorfastness data

Can guarantee volume of fabric through a written contract

A good rule of thumb when you’re starting out as a new brand may be to work with a fabric mills core fabrics. Mills will have many fabrics that they will carry over season after season. You should ask the mills which these fabrics are, and how long they have been running for.

These core, consistent fabrics also often have the advantage of being available in multiple colours. Therefore, if you’re a new brand that maybe can’t commit to enough metres to dye in your custom Pantone colour, you may be able to select from a number of stock colours to use for your product and collection.

Test Beyond the Sample Roll

It’s often overlooked that when you prototype a product, it’s coming from a sample roll. A sample roll or “test yardage” is a small batch of fabric produced by the mill for the purpose of;

Prototyping

Fit sessions

Lab dips (colour approvals)

Pre-production mock ups and salesman samples

It’s vitally important to understand that a sample roll is usually under lab controlled conditions and because it’s a small batch, it can be closely monitored, often by hand. At bulk production, the fabric is being built on an industrial scale, and therefore the chance of variance is greater.

Small discrepancies between sample and bulk fabric can impact things such as fit, colour, hand feel etc. Here is a table highlighting some common issues and its impending result;

Best practices for bridging sample to bulk

Always request bulk roll test swatches before finalizing production specs

Run key lab tests (e.g. stretch recovery, GSM, pilling) on both sample and bulk yardage

Use colour evaluation tools (lightbox/booth) to check lab dips vs. production runs

If using zoned materials (e.g. mesh + softshell), validate interaction across all roll sources

A sample roll is often necessary, but treat it like a demo. It’s great for early decisions, but not a guarantee in how your garment will behave at scale.

Final Thread

When you start your brand, it’s easy to look at things on a micro-scale, but I would argue that implementing systems from day that support long term growth and scalability of product can only be a good thing.

From the foundational fit blocks that keep sizing consistent, to component libraries and modular design thinking that allow you to build faster without sacrificing identity, these are things that help support growth.

The best-performing sportswear brands think beyond aesthetics. They continually look improve their product, and treat every prototype like a test case, not a final product.

This process isn’t fast, nor is it easy, and I understand the desire to try and rush products to market. However, it will save you time, money and brand equity in the long run. If you build the systems to scale early, you’ll thank yourself when demand starts to rise.

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to reach out to me directly at seb.beasant@torsa.co.uk