Game-Changer's Guide: Essentials for Creating Apparel Collections.

The art of building an apparel brand comes down to knowledge, experience and some trial and error. This is my guide on how to navigate the process.

Topics

♻️ Building a product range with emphasis on consistent product narrative

🏅 Developing hero products and how to scale them effectively

🧶 The art of fabric consolidation and why it’s a necessity for start-ups

🎨 Exploring the logistical side of colour and supplier workarounds

🏬 Building a range for wholesale

There are certain things I wish I knew when I started Torsa that would have saved me time, money and a whole lot of pain. People say you must learn from your mistakes, and if that’s the case, I had a lot of learning to do.

When you build an apparel brand from scratch, there are a series of steps and processes you have to go through from concept to launch. This article aims to share with you certain insights I had when building Torsa that would have made the process far more streamlined and effective. Most of this will revolve around the manufacture of product; design, sourcing and development, but i’ll also discuss logistics, strategy and distribution in detail.

Range building

Building a collection requires thoughtful planning. It’s not simply a case of designing some styles you like and launching them. There are a number of elements to consider which will have an impact on the final range of products. This is even more crucial for a start-up because you don’t have the resources to get it wrong.

Customer value

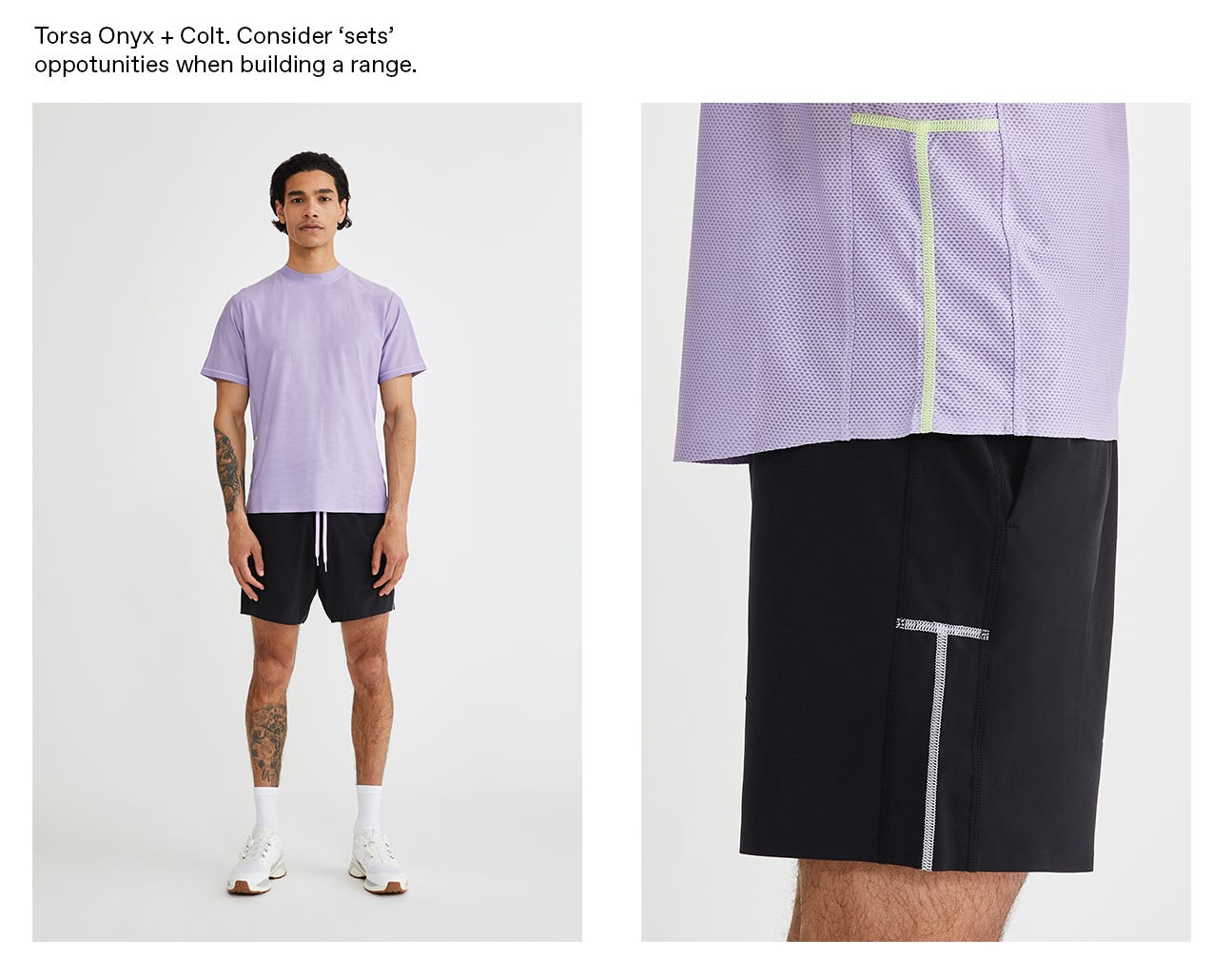

What value is your range bringing to your customer? Are you offering something unique that they can’t get elsewhere? When designing a range, consider the collection as a whole. You could look to build a range based around outfitting or sets. An example of this would be designing a lightweight training short with a featherweight training t-shirt. These are then merchandised together, shot and marketed together to build a story around the pair of products.

In our case, we created the Onyx T-Shirt and Colt Training Shorts to be worn together. You’ll notice, we even kept the T-stitch consistent in its application (flatlock) on both products and integrated a side seam for both so the T would flow cohesively from one style to the next.

Creating sets of product like this isn’t just good for merchandising purposes, it can also have a big impact on your AOV (average order value). When you merchandise and market products together, customers are inclined to order the outfit as a whole. We have actually had more orders for the Onyx T-Shirt and Colt Shorts bought together than we have individually. This has had big impact on our bottom line - (greater AOV has led to higher gross margin (due to offsetting the shipping costs), but crucially a higher customer lifetime value.

Hero product

When you’re designing a collection, consider the opportunity for hero products. I’ve explained the power of hero products, but also its limitations in a previous article which you can read below;

Hero products, in essence, are your business driver. It’s what your brand is known for, and it can be seen across industries all over the world. As you scale, your brand can have multiple hero products, but as a start-up (if you decided to employ this approach), focus on one product that drives your business forward.

There’s a few rules I like to put in place when building your hero products;

High margin

Achieving a high margin is going to drive profitability forward exponentially. If you can find a way of achieving a high gross margin for your best selling product, you’re going to have the foundation for a solid business. There are a number of ways you can achieve a high margin; from cheaper manufacturing, sourcing economical fabrics, charging a higher price point, and so on. However, you must consider that this product is your hero product, and therefore needs to perform from a quality and functional standpoint.

Adaptability

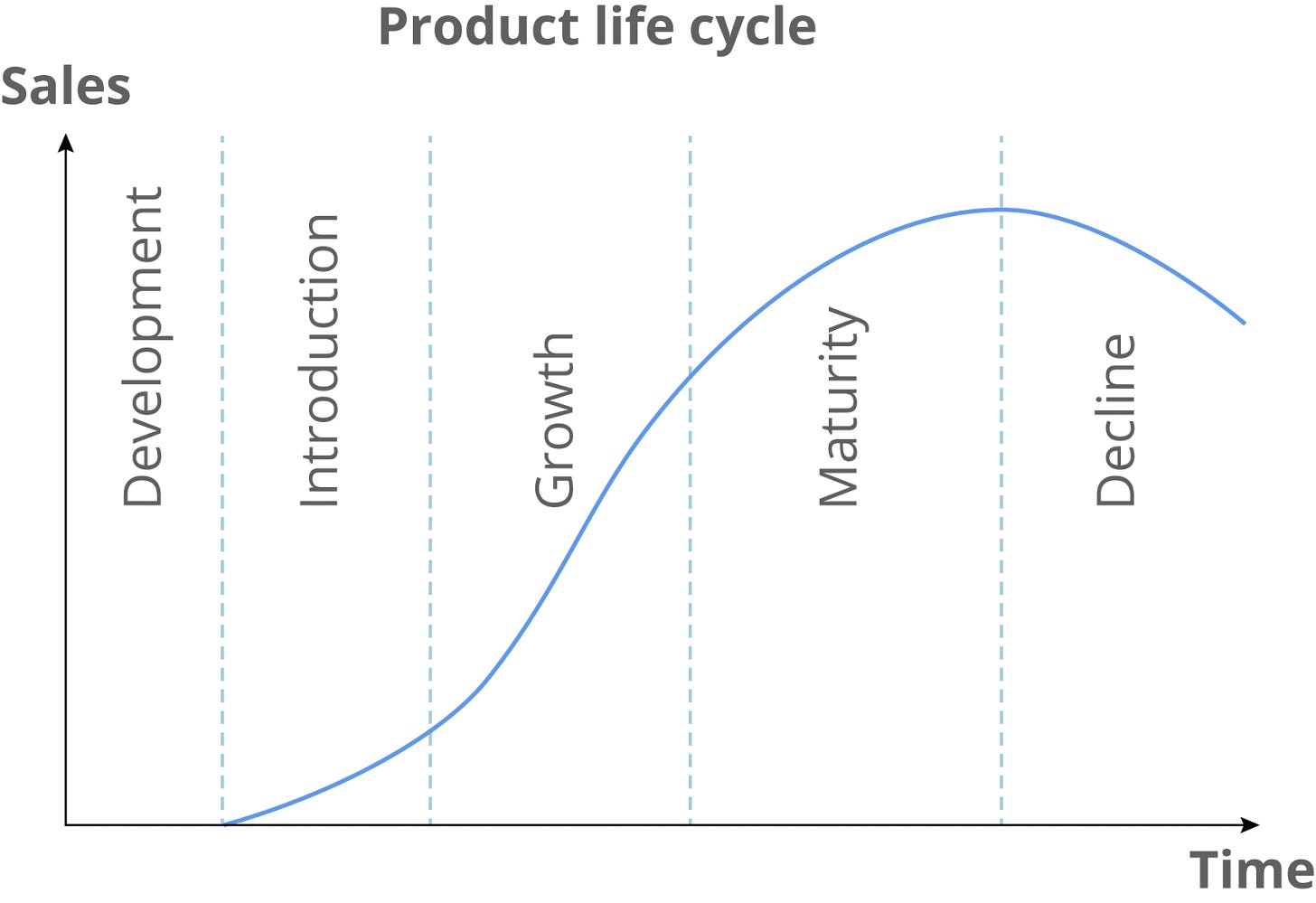

Can you make your hero product adaptable? The issue with many hero products is that they come and go, following a predictable product lifecycle seen below;

There may be ways to prolong this cycle through marketing, or entering new geographic markets, but a great way of getting the most out of your hero products is adaptability.

Take the Fjällräven Kånken, the lifeblood of the Swedish outdoor brand. Although originally known for their hard-wearing, functional outerwear for Swedish hikers, the global success of the Kånken has transformed the focus of the business through the backpacks success in urban markets and metropolitan cities. Undoubtedly the brands hero product, Fjällräven didn’t rest on their laurels when it came to capitalising on the Kånken’s success. Instead, they opted to adapt the Kånken framework into multiple variations of the product.

This approach gave those consumers who loved the Kånken Original the opportunity to double-down so to speak, and offer them variations of their favourite product. It also meant Fjällräven could acquire new customers that maybe were interested in the shape and style of the Kånken Original, but were in the market for a Weekender or Sling Bag for example.

Versatility and scalability

Before deciding on your hero product, explore just how versatile your product is. By this I mean, are you creating a product that can be easily scaled through something as simple as colour for example? There are certain categories that this is easier to achieve than others.

For example, if you’re a sportswear brand producing running apparel and accessories, making a hydration vest a hero product may not have the same scalability as something like a unique Merino wool fabric. Whilst a Merino wool fabric can be adapted in multiple colours, prints and styles, a hydration vest simply doesn’t have the same opportunity to scale.

Also, unlike a Merino wool t-shirt, the likelihood of a customer buying multiple hydration vests is slim. If it’s your hero product, you want to maximise its potential return as much as possible, rather than limit it. Satisfy Running for example made Cloud Merino™ their hero fabric when it came to their cold weather offering. This lightweight fabric from Japan uses a super fine crimp and one of the softest Merino wools in the world.

Firstly, this was a great storytelling aspect, but using the same material allowed them to scale Cloud Merino™ easily through colour, print and different product styles, in what’s called fabric consolidation, which I will touch on next.

Fabric consolidation

One of the most critical components of building a range, and something I wasn’t aware of when I first launched Torsa, fabric consolidation is crucial when starting out, and scaling your product offering. Both sourcing and developing product are incredibly difficult. You only have to look at our development process to understand the time, work and money that goes into it.

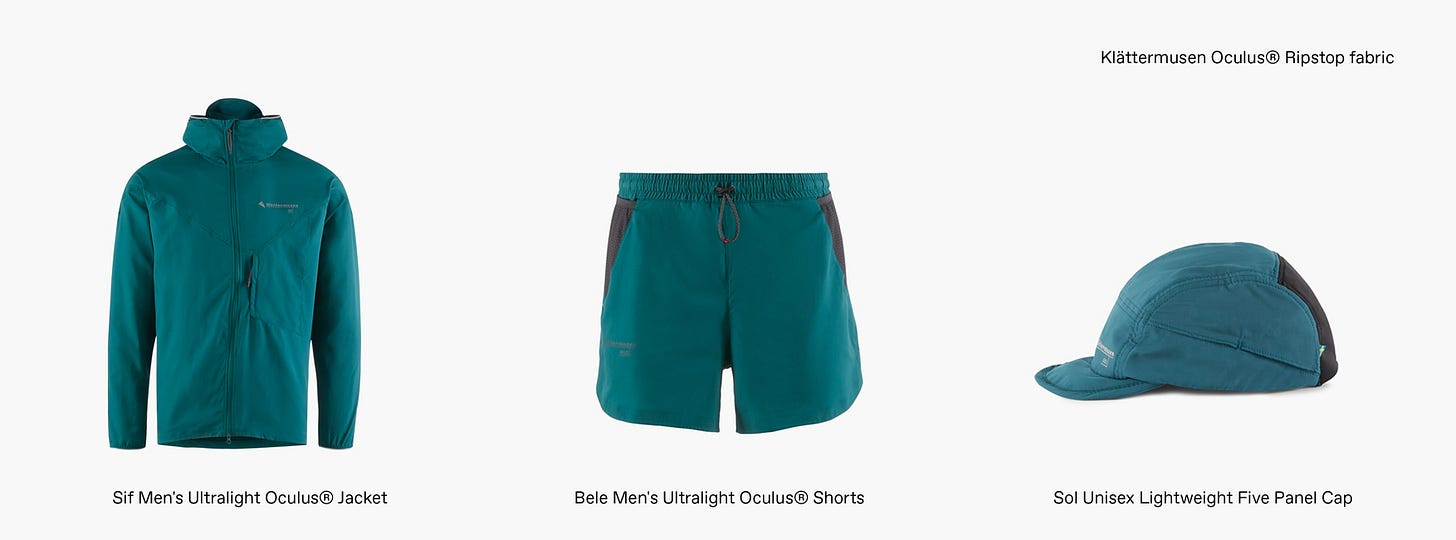

Fabric consolidation is one way to minimise time, reduce the margin for error and build a consistent and cohesive narrative. When I talk about fabric consolidation, I am referring to using one fabric across multiple styles.

This approach is used throughout your favourite brands, even if it’s not clear to the customer. Why this strategy is so commonly used is that once you have a fabric that works, you can be confident it will work in other styles, where the goal is to provide the same outcome to the customer.

Let’s take a lightweight nylon fabric for a run capsule collection. Let’s say the primary goal is to find a fabric for running that is super lightweight, breathable and water-resistant. If we come at it from a range building lens, we can assume that a lightweight woven fabric with a DWR coating could be used for a pair of running shorts, a running jacket, and a running cap. This fabric fits the bill for all of these styles, so instead of sourcing three similar fabrics doing the same job, just use that one perfect fabric which will fulfil the needs for all.

One other huge benefit of consolidating your fabric, especially as a start-up, is tackling the problem of MOQ’s. Fabric minimum order quantities are an inevitable part of the manufacturing process. Let’s say you’re a start-up and found a factory that can produce 100 units of a certain style, with a consumption of 1m per style, ie. you need 100 metres of fabric to produce 100 garments.

However, as is often the case with fabric mills in Europe, you’re forced to order 300m of fabric. Therefore, you have a choice of increasing your production to 300 units (tripling your production costs), or, buying 300 metres, producing 100 units, and keeping the leftover 200m in storage – not a financially viable option for a start-up.

However, let’s say you consolidated that fabric and used it across three styles. You then have met the MOQ with the fabric mill whilst producing three styles out of just one fabric – a financial and commercially clever decision.

Designing your collection around distribution strategy

One crucial factor to consider when designing your collection is your distribution strategy. If we focus on wholesale for example, depending on the retailer, but you probably want to present 16+ SKU’s for your first season.

A SKU essentially means one unique product. However, this can be a variation of the same product, ie a pair of shorts in three colours would constitute as 3 SKUs.

Of course, when you’re presenting to retailers, they want depth as well in the collection, ie. multiple different categories to buy from. Their job as buyers is to build a cohesive range of product which is going to resonate with their customer.

It’s important to consider this when designing for wholesale. Retailers buy seasonally, and therefore, as an example, you don’t want to present a cold weather running collection for SS24. That is why managing your timelines with design, sourcing, sampling, and product development are so crucial. You don’t want to miss the retailers buying window because of poor planning, but this can so easily happen due to unforeseen circumstances.

The Colour Conundrum

An element of sampling which is often overlooked, yet vitally important, is this practical element of colour. When you design a collection, building a colour palette is of course a crucial stage. However, when you’re developing samples for wholesale, it’s not as simple as getting all the colours you want during the sampling stage. What do I mean by this?

Well, let’s consider you introduce a running jacket in three colours. You have your Pantone colours selected and you’ll go through what’s called a lab dip approval stage. This is where the fabric mill will dye a small swatch of your chosen fabric in your selected colours, and you’ll receive something like this;

At this stage, you can approve the selected dips, or maybe it turns out one of the colours you have selected doesn’t look quite as you thought, so you get a re-dip in a different Pantone. Nonetheless, in terms of colour reference, this is what you will receive to sign off.

However, let’s assume you are showing to wholesale buyers at the end of the season and want to show them the jacket in all the correct colours.

It’s not as simple as saying, we want 2m of colour X for sampling. It’s not economical for a fabric mill to dye just a few metres for sampling, and therefore all mills will have something called SMS yardage. SMS refers to “sales man sample” yardage, and it will have a MOQ which in my experience can range from 70m to 300m, depending on the mill and region.

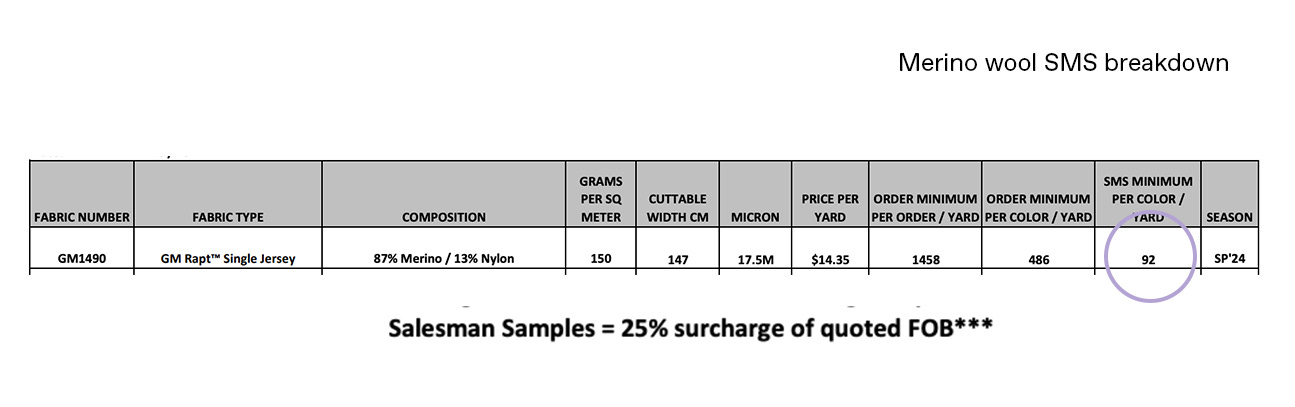

For example, let’s take a practical example from Torsa. In relation to our Merino wool fabric, the terms of trade for SMS yardage can be seen below;

Just to break this down, if we wanted to order a colour of our choice in this fabric, we would have to commit to 92 yards. And, although the price for a bulk order would be $14.35 per yard, SMS orders are charged at 25% more. Therefore, we’d be looking at $17.93 per yard ($14.35 x 25%).

The total cost for 92 yards of SMS yards therefore would be 92 x $17.93 = $1,649.56

Now consider you do that for three colours, it would equate to $1,649.56 x 3 = $4,948.68. You are essentially investing in nearly $5k worth of SMS fabric to produce styles for wholesale that retailers may not even buy.

For bigger brands, with a network of wholesale suppliers, they can easily absorb this cost on the premise that they will receive multiple orders from wholesalers which will quickly offset all of the SMS yardage they commit to. For a start-up though, this approach clearly isn’t feasible, nor financially viable.

An alternative approach

So, what can you do as a start-up to get around this issue. In my opinion, there are two approaches you can employ;

Plan and buy from stock

This approach is pretty simple. You plan your colour palette around the fabric mills stock colours. Most of the fabrics you source will have stock colours; essentially fabric on hand in one colour that you can sample. The obvious main issue here is that you’re range is dictated by what the mills stock colours are. With colour being such an important element in design, this approach severely limits your brands ability to built a colour palette in line with your brand.

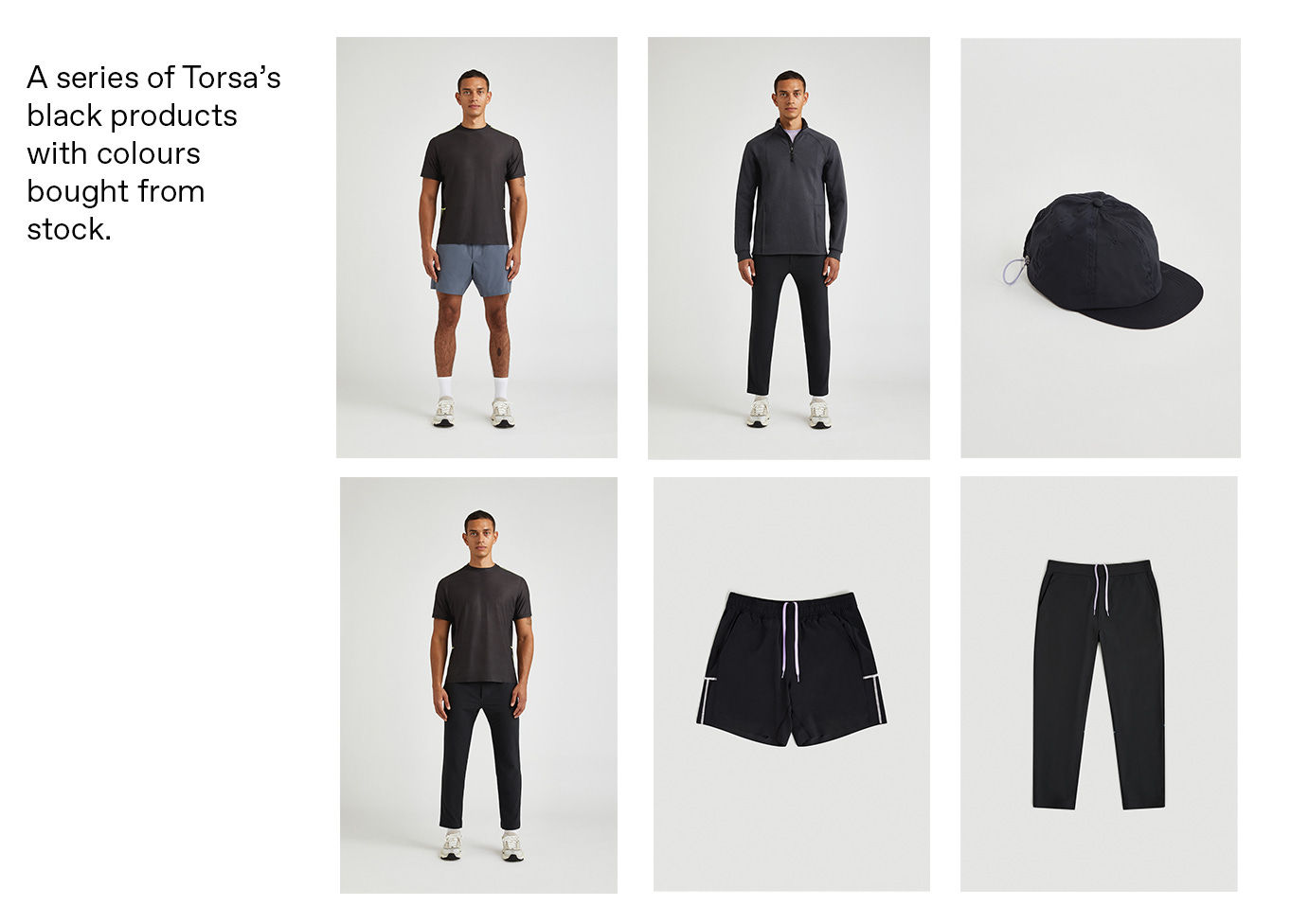

Having said that, black is often the most popular stock colour that the fabric mill will hold in certain fabrics, and this can be super useful for styles that you had planned to introduce in black. Consider wholesale commerciality when producing a range. Yes, black can be boring, but it is often the best selling colour for things such as shorts, tracksuit bottoms, and jackets. Therefore, including it in your range should certainly be a consideration and buying from stock (as often it’s black) allows this.

Here is a quick breakdown of why buying from stock can be a useful option;

Pros

Usually black is the stock colour on hand. If you aim to showcase your style in black, buying from stock is often a great option.

No price increases, surcharges or financial implications for sampling the stock colour.

No long lead times as you’d have to encounter if you placed an SMS order for your own Pantone.

Cons

Very difficult to build a whole range based on stock colours as you are restricted by the fabric mill’s choice.

There are many different shades of black and in an ideal world you want to have them consistent across different fabrics and styles. This can’t be achieved when buying black stock colours, as they will all be slightly different shades of black.

Can lead to a longer time sourcing as you try and seek out fabrics with the ‘right’ stock colours. You may come across an amazing fabric but can’t use it because you don’t like the stock colour.

Order ‘tagging’

Tagging onto the back of an order is a really useful approach for start-ups. It’s something I have used in the past and will continue to use moving forward.

Order tagging

This refers to ‘tagging’ onto the back of other brands orders that are currently in sampling or production.

Let’s say you have found a fabric you like but you don’t like the stock colour, or the mill doesn’t currently have any stock on hand. You can ask the fabric mill if they have any upcoming orders from other brands that you can ‘tag’ onto.

In this case, because you only need a few metres for sampling, it is easy for the mill to add a few metres onto another brands SMS or bulk production order. They then can cut off a few metres and send it to you for sampling.

Pros

More likelihood of a colour other than just black, but depends on the brand of course.

Maybe there are three brands that have upcoming orders - you have three potential colours to choose from.

No surcharges.

Cons

You are completely reliant on other brands colour choices, you of course, have no say in the matter.

You are also reliant on other brands sampling and production schedules - a fabric mill may say they don’t have any orders of that fabric, or the order won’t be ready for another 6 weeks.

Some fabric mills may not want to do this, showing integrity to the brand that placed the initial order.

Final Thread

Developing a sportswear collection understandably has its fair share of challenges. This article touches on just a few important elements to consider, with experiences and learnings from building Torsa.

Your distribution strategy plays a significant roll in your overall brand strategy. Like I mentioned, if you want to build a range for wholesale, you will want to plan significantly for this approach. Even the sourcing stage is going to be of critical importance for a wholesale strategy as you have to take into considerations things such building from available stock colours, tagging onto orders and the art of fabric consolidation.

Maybe you want to go down the route of building a hero product. Firstly, it’s a good idea to plan just how this product is going to become your ‘hero’ product. What is special or unique about it? Is it versatile, scaleable and does it have a high enough margin to drive your business’ profitability? How are you going to market it? All these things should be considered before diving into actually developing something.

Ultimately, understanding these steps comes with experience and actually going through it. It’s really helpful to have people around you that have the knowledge and insight, and can advise you on the processes. If you need any advice from me, please feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn here.